Last week I told you the secret to success was going into massive debt and then digging your way out. If you make it, then you will have the resources to continue to live large. If you don’t, you will be bankrupt.

Debt, like a screwdriver or a chainsaw, is a tool. When I was a boy, my dad had a spring-loaded screwdriver called a push drill driver. You push down and the screw turns. It didn’t work very well because, inevitably, the head of the screwdriver would slip off the screw with spring-loaded force.

But it was a wonderful gizmo, and I took no end of pleasure in playing with it. One day I was building a tree fort, and I positioned myself in such a way that I was pulling the screwdriver toward me. The head slipped off the screw and embedded itself in my eyebrow, blood flowed freely as head wounds do, and my mom flipped out.

Stanley Yankee No. 130A Push Drill Driver

Stanley Yankee No. 130A Push Drill Driver

It wasn’t the screwdriver’s fault that I almost jabbed my eye out. It was my own damn fault for using the tool wrong.

Money is the same way. You can use it to work for you or against you. We all know that some form of debt is bad and some is good. Most people would say that taking on $500,000 in debt to buy a house and pay it back once a month for 30 years is good debt.

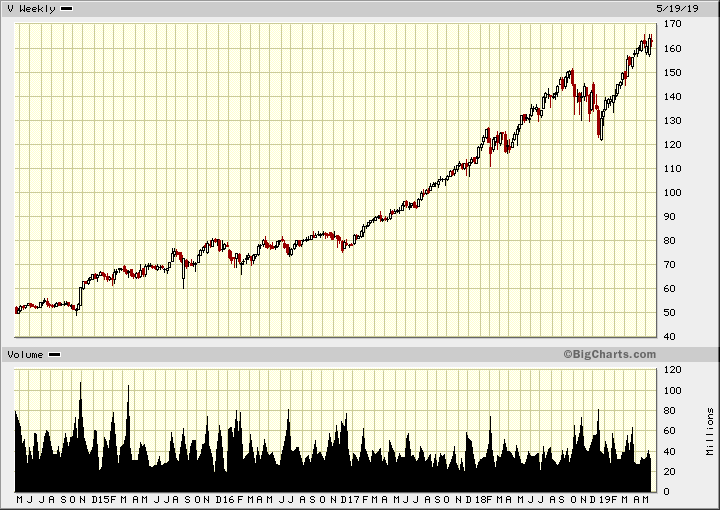

But if you are paying 4% on that mortgage you bought in 2012 and now have lots of equity, why don’t you take a loan against it and buy Visa (NYSE: V), which has a fantastic business and only goes up?

If you would have done that in 2016 using 100% margin, you could sell now and almost pay off your mortgage.

That would be good debt unless it went bad. Say there was another event, like 2000 or 2008…

You lose your job, the value of your house plummets, and Visa’s share price gets cut in half. Well, if that happens, you just declare bankruptcy, dust yourself off, and wander off down the road. If you did it big enough — say you bought 30 houses — maybe you could get a book deal.

Why more people don’t do this I have no idea. I suppose it is a matter of scale. You and I won’t bet the proverbial house on a stock because people would think badly of us.

Your father would cut you out of the will because you were irresponsible. Your mother would talk badly about your money-handling skills at her bridge parties, and your children would be upset about the loss of their college fund.

But if you were big, really big, like a company or a government, you could go into massive debt without a care in the world.

Our analysts have traveled the world over, dedicated to finding the best and most profitable investments in the global energy markets. All you have to do to join our Energy and Capital investment community is sign up for the daily newsletter below.

Take China for instance. China is running into the wall of diminishing returns. It used to grow 10% a year. Now, it grows 6% or even less.

To continue its upward surge, it started to borrow money — lots of money. Some estimates are that China owns more than 320% of its GDP.

At what point is it too much?

Here is a chart The Economist published a few years ago showing the point at which debt overwhelms.

You can see in most instances it is between 160% and 220% of GDP. Mexico is an outlier.

As I said, this chart is three years old. Chinese debt is much higher today, well above the point of no return.

And this isn’t just theoretical. The first domino has already dropped. On Friday afternoon, before the three-day weekend, it was announced that Baoshang Bank Co., a regional bank in China, has failed.

According to Reuters:

The central bank and the banking and insurance regulator are assuming control of Baoshang Bank Co. for one year because it poses serious credit risks, in the first government takeover of a lender in more than two decades.

Bloomberg goes on to write:

“Low quality, small regional banks are unlikely to pose systematic risks to the financial system or the operations of the big SOE and joint stock banks,” analysts Linda Sun-Mattison and Jason Li wrote in a note on Monday. “However, the bail out of Baoshang Bank, a rare move by the government, and the involvement of CCB will no doubt heighten investor concerns over SOE banks’ risk exposure to national service.”

I can distinctly remember analysts on CNBC and in the Wall Street Journal telling me something similar in 2008 right before the biggest recession in 80 years.

At some point, China has to deleverage. How that happens, and who is hurt, will be the story of the next market crisis.

All my best,

Christian DeHaemer

Christian is the founder of Bull and Bust Report and an editor at Energy and Capital. For more on Christian, see his editor’s page.